As noted in my initiation report, I entered a long position in Stellantis in April 2024. At the time, this was a high conviction investment for me; the Company was trading at a FCF/EV yield north of 20%, had an expected return of close to 6x cash-on-cash, and the downside was mitigated by a capital return program that equated to 18% of the market cap each year, a portion of which produced a dividend yield of 9%. The attractive financial profile was bolstered by a strong technology portfolio that positioned STLA well for automotive industry trends and avoided the classic “melting ice cube” pitfall of value investing.

And yet, a little over a year later, I have completely exited my position in the Company with a significant loss on my investment. What changed? In reviewing my decision to exit, there were eight individual factors, including mistakes in my process that produced this outcome. These points are as follows.

As a result of industry-wide supply constraints during COVID, management was able to push higher priced vehicles into the dealer channel, driving ASP growth in 2022 that produced robust revenue growth while maintaining margins despite lower production levels.

Once demand began to normalize in 2023 as a result of higher interest rates, management offset ASP declines by stuffing the dealer channel with inventory. This produced revenue growth of 5.5%, as volume growth of 7.6% offset an ASP decline of 2.9% in the same period. The higher volume also helped drive gross margins above 20% and EBIT margin close to 12%. In short, Stellantis the manufacturer was flattering itself to public market investors at the expense of its dealer network.

As the automotive market cooled off and supply normalized, dealers found themselves flush with inventory, much of it now the wrong type due to the affordability constraints now affecting the market. Stellantis had to respond with pricing concessions and dealer rebates to help move product.

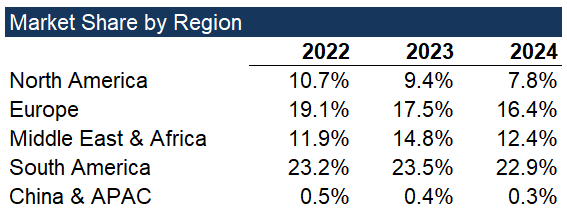

The above factors combined to produce consistent market share declines in the Company’s major markets, as outlined in the following table. We also gave credit to management’s belief that they were aware of the market share issues and were resolving it, given their past performance in driving synergies post-merger and resulting corporate profitability.

Once the end demand issues flowed through to Stellantis in 2024, the impact was significant. Revenues declined 17.2%, driven by volumes decreasing by 12.9% and ASPs dropping by 6.3%. Given the significant leverage in the business, this led to gross margins dropping 700bps to 13.1%, EBIT margin to fall 950bps to 2.4% and free cash flow to turn negative.

Management had to walk-back a target of double digit (10%+) Adjusted Operating Income (AOI) margin for market cycle bottoms and 2024 less than six months after announcing the target in June 2024, significantly reducing management’s credibility.

The CEO of Stellantis, Carlos Tavares was fired in December 2024 due to disagreements with the board on strategy, adding additional question marks on the management team’s capabilities.

Separate to the issues at Stellantis, I found my portfolio significantly over-weighted to automotive names. In addition to Stellantis, I had positions in Ferrari, Porsche, and ON Semi. Taken together, many of these individual positions stopped making sense at the portfolio level.

Conclusion & Lessons Learned

So what is the aggregate damage done as a result of this investment? My average cost base was roughly $18.75/share, and my aggregate exit price was $11.05/share, resulting in a 41% loss of capital - pretty terrible for a one year return!

Despite the loss, I believe there are two very clear lessons that I’ve paid dearly to learn.

First, my investment in Stellantis has reinforced the importance of channel checks when considering an investment in any business that relies on distributors to get the majority of its product to market. Public companies can dance a littler longer after the music stops at the end buyer level, but reality always catches up eventually, an experience that is no fun for investors on the wrong side of the cycle. I’ve seen this process happen at another investment that didn’t go well for me (Enphase - expect a similar report on this particular investment in the near future), so it’s fair to say that I no longer deserve any grace for making similar mistakes in the future. What I will acknowledge is the difficulty of getting this part of the diligence process right as an individual investor. Sure, I could subscribe to an expert network and call a bunch of dealers to get their perspective, or travel to a bunch of dealers in Stellantis’ major markets to get a sense of inventory levels, but this is just not cost effective as an individual investor. Practically speaking, what this means for me is just avoiding companies that derive a large portion of their business from selling to distributors, particularly in highly cyclical industries. However, as a professional investor with access to more resources, I would spend far more time at this part of the diligence process going forward.

Second, this experience has impressed upon me the importance of thinking about my investments at a portfolio level. In other words, I made the classic analyst mistake of thinking about each investment on its individual merits without thinking about the implications of what an individual investment means for the portfolio as a whole. If I had considered my existing exposure to automotive (Ferrari and ON Semi), and asked myself whether an investment in Stellantis meaningfully improved my exposure to the segment in terms of competitive position, expected return, and financial profile, I likely would not have made this investment in the first place, preserving a material amount of capital in the process.

While losing capital is always frustrating, the ability to learn from mistakes always presents a silver lining that can compound to influence my future investment decisions. Hopefully my losses can help you avoid a few stinkers of your own.